Take a Trip on a Survey Ship:

USNS Michelson (T-AGS-23)

For 17 years (1958-75) Michelson collected data about the earth's oceans and created navigational charts.

John Hansen was a member of the ship's Navy oceanographic team from late 1962 through 1964.

Here are his recollections and reminiscences of people, places and ports of call.

For 17 years (1958-75) Michelson collected data about the earth's oceans and created navigational charts.

John Hansen was a member of the ship's Navy oceanographic team from late 1962 through 1964.

Here are his recollections and reminiscences of people, places and ports of call.

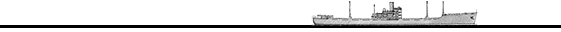

Starboard side profile of USNS Michelson (T-AGS-23).

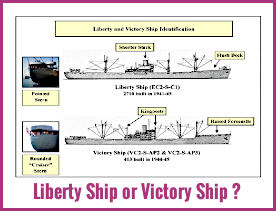

Launched in 1944 as SS Joliet Victory, this VC2-S-AP3 class vessel was converted to a deep ocean survey ship in 1958.

The kingposts just forward of the superstructure were removed. Only the #4 hold retained its cargo handling gear.

Not pictured are the #5 and #6 lifeboats, on each side just aft of the #4 hold.

The OC Hoist was installed later at the stern.

John A. Hansen Update

It is with a heavy heart that the Hansen family informs you that John passed away peacefully in January 2023. We know how much John enjoyed managing this website and connecting with all of you over the years. Thank you so much for your enthusiasm.

If there is anyone interested in taking the baton from John and keeping this website active, please reach out via email to his son David (davidjohnhansen@hotmail.com) and include MICHELSON in the subject.

All the best, The Hansen Family

Blue and Gold Stack

So, what does USNS mean? That’s United

States Naval Ship, meaning a non-commissioned

Navy ownedvessel operated by a civilian merchant marine crew rather

than by naval personnel. These are generally

auxiliary support ships: oilers (refueling tankers), transport ships

and replenishment

vessels supporting the fleet. Some are hospital ships or special

mission ships, including those

conducting ocean surveys.

So, what does USNS mean? That’s United

States Naval Ship, meaning a non-commissioned

Navy ownedvessel operated by a civilian merchant marine crew rather

than by naval personnel. These are generally

auxiliary support ships: oilers (refueling tankers), transport ships

and replenishment

vessels supporting the fleet. Some are hospital ships or special

mission ships, including those

conducting ocean surveys. Why the stripes on the stack? First of all, blue and gold are the official colors of the U.S. Navy. All shipping companies and cruise lines have their own proprietary stack insignia, helping in identification and as a form of advertising. Except for hospital ships, which are painted white, a USNS vessel generally looks pretty much like the regular navy except for having blue and gold stripes added around the smokestack. This is the insignia of the Navy's own sea transport company the Military Sealift Command (MSC), previously known as Military Sea Transportation Service (MSTS).

MSC/MSTS's forerunner the Army Transport Service once operated troopships. This business was turned over to the Navy in the late 1940s.

MSC operated ships have a "T"

prefix before their classification symbol and hull number. Michelson's

was T-AGS-23.

MSC operated ships have a "T"

prefix before their classification symbol and hull number. Michelson's

was T-AGS-23.Those ships designated USS (United States Ship) are commissioned, meaning they are manned by traditional crews of navy officers and enlistees.

Today, with defense budgets shrinking, more navy auxiliary ships are being operated more economically by MSC with civilian merchant marine crews.

Never Sail on Friday

|

| "Blue Peter" means ready to sail |

Thomas Gibbons addressed this well in "Boxing the Compass" (c. 1880):

"There is but a plank between a sailor and eternity; and perhaps the occasional realization of that fact may have had something to do with the broad grain of superstition at one time undoubtedly lurking in his nature. But whatever the cause, certainly the legendary lore of the sea is as diversified and interesting as the myths and traditions which haunt the imagination of landsmen, and it is not surprising that sailors, who observe the phenomenons of nature under such varied and impressive aspects, should be found to cling with tenacious obstinacy to their superstitious fancies. The winds, clouds, waves, sun, moon and stars have ever been invested with propitious or unlucky signs; and within a score of years we have met seamen who had perfect faith in the weather lore and traditions acquired during their ocean wanderings."Here are some examples of common nautical beliefs:

- It was considered bad luck for a sailor to encounter a cross eyed or flat footed person, one with red hair or a priest or other clergyman while his way to his ship.

- A ship could not be renamed without following a prescribed official ceremony.

- Women aboard a ship would anger the sea and bring misfortune.

- Hearing bells meant death aboard ship, A ship followed by a shark meant someone was going to die.

- Killing an albatross or a dolphin brought misfortune.

- It was unlucky to bring scissors or an umbrella aboard. Whistling on board would bring storms.

- Trouble came to those who cut their hair, beard or nails while at sea.

- One always crushed egg shells before throwing them away to avoid witches using them as boats.

- Harming sea gulls was forbidden as they were thought to hold the souls of sailors lost at sea.

- Sailors had a great deal of faith in odd numbers. Thus, naval (and other military) salutes included an odd number of guns.

- Ancient Greek mariners thought lightning or an an eclipse of the sun or moon to be a dire portent of evil.

- Icelandic sailors predicted shipwreck if a crescent moon with its horns pointed toward the earth was sighted.

Some quotations regarding sailing on Friday:

- "As for sailing on Friday, that was out of the question. No one did that who could help it," - Cooper (1798)

- "Seldom would a seaman then sail on Friday". - Thatcher (1821)

- "He [the sailor] will never go to sea on Friday, if he can help it". - Cheever (1827)

- "Many a ship has lost the tide which might have led to fortune because the captain and crew thought it unlucky to sail on Friday". - Southey (c. 1840)

- "A Friday's sail will always fail." - Cheales (1875)

The Norse water goddess Freya was regarded as sacred by sailors, making her namesake day, Friday, holy, thus unsuitable for beginning a voyage. Chaucer, in the Knight's Tale (1386) described the day's variable weather, claiming that Friday is the best or worst day of the week. This observation is echoed in English folk proverbs of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Mariners could point to occurrences which they thought clearly validated their beliefs, listing all sorts of vessels that met their doom because they got underway on a Friday. Some were never seen again, lost at sea with all hands. Other Friday sailings sank or were wrecked on a Friday as well.

The other days of the week were generally regarded as safe sailing days. Sunday seems to be the best day in most cultures: "The better the day, the better the deed". Wednesday and Thursday were dedicated to the Norse gods Odin and Thor, respectively, both of whom were especially beneficial to mariners. In Spain Tuesday is unlucky: "Tuesday, don't marry, go to sea, or leave your wife".

Certain days of the month were unlucky exceptions. Some references indicate that the 13th of the month brought storms. Others say that the 4th, 5th, 13th, 16th, 19th and 24th were unlucky days. Another says of the 29th: "And on thy dark ocean way, launch the oar'd galley - few will trust the day".

I'll be in My Stateroom

Enlisted men had fairly spacious four man staterooms with built in bunks, bookshelves, large lockers, a sink, a writing desk and a connecting bathroom, known nautically as the head. Each bunk had a reading light and there were storage drawers under each set of bunks. There was plenty of space for uniforms and civilian clothes. Everything except for chairs and the wastebasket were bolted down in case of heavy seas. We also had a lounge with books, card tables and comfortable chairs. The ship’s dispensary and a little hospital were also on the second deck.

Most officers, chief petty officers and civilians had two man rooms. They had stewards to make up their bunks and clean their rooms. Enlisted guys did all this themselves.

When I was aboard Michelson the staterooms were not air conditioned, but had forced air ventilation with wall mounted fans. Air conditioning, sometimes really cold, was provided in work spaces to keep the electronic stuff cool.

Some thought went into making the accommodations comfortable. Survey ships spend a lot of time at sea.

Dinner is Served

"Gentlemen, decorum must be maintained in the dining room". This was our messman's customary request when his customers became a bit noisy. Harry was an older, crusty guy from New York who served the navy enlisted men. Yes, served. Being passengers on MSTS, the navy's own steamship company, in 1962 and '63 Harry was our waiter.

"Gentlemen, decorum must be maintained in the dining room". This was our messman's customary request when his customers became a bit noisy. Harry was an older, crusty guy from New York who served the navy enlisted men. Yes, served. Being passengers on MSTS, the navy's own steamship company, in 1962 and '63 Harry was our waiter. Harry's domain seated perhaps 16 to 18 at a time. There were four tables covered with red checked tablecloths, and real chairs. Each table had a little steel rim around the edge to keep plates from sliding off. Yes, plates, rather than steel trays found on navy ships. No chow line here! The breakfast menu included eggs to order, pancakes and sometimes even that famous creamed beef on toast. There were always three entree choices at lunch and dinner on the printed daily menus. Meat dishes could be ordered "wet" or "dry", which meant, in Harry's messroom vernacular, with or without gravy.

|

| A can of Norge Fiskeboller (fish balls). |

One of the cooks was also a baker, so we always had fresh bread, cakes and pies. The cooks left out cold meats and cheese plus plenty of coffee for those on watch at night. Overall, MSTS food was pretty good. One could easily gain weight. Nevertheless, some grumbled about the food quality, blaming the chief steward's close attention to budget, referring to him as the "cheap steward".

There was one no sale menu item. Somebody had over provisioned on canned "norge fiskeboller" in Bergen. This codfish product appeared on the dinner menu at least once a week. I'm the only one who ever ordered norge fish balls with brown gravy. Kind of looked like those IKEA meat balls but were not very appetizing. They dumped what was left of them in the galley after the ship reached New York.

When the seas got really rough, Harry (the messman) would add extra anti-sliding protection by soaking the tablecloths with water. Unlike the ones based in Oakland, MSTS Atlantic cooks were always able to produce hot meals even in the heaviest of seas.

A mess assistant helped Harry serve then washed dishes in the adjacent scullery. The navy chief petty officer(s) had a little one table mess room next door. Messmen never get a day off, even in port, as the crew and passengers need to be fed. Sometimes they would get someone else to cover for them so they could go ashore during the day.

Despite his gruff manner, Harry was fond of classical music. Whenever he requested it, we played an LP record of Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade on the ship's entertainment audio system. He said that it was his favorite music.

Clicking on the elegant menu cover (at right) will reveal the repasts served on two nights in 1961 aboard Michelson, as posted by Lyle Hildebrand on the TAGS website, shamefully liberated. Neither dinner menu included norge fiskeboller. Apologies to Cunard Line for lifting their 1908 RMS Mauretania menu.

An Old Ship

SS Joliet Victory

when operated by Alaska Steamship Company. Date and location unknown.

While

strictly functional,

Victory ships had a certain style, with a raised

bow and rounded "cruiser stern" plus a

forward superstructure curved on both port

and starboard sides, sort of a small attempt at graceful streamlining.

Most Victory ships were named for American cities, others for colleges

and

universities.

While

strictly functional,

Victory ships had a certain style, with a raised

bow and rounded "cruiser stern" plus a

forward superstructure curved on both port

and starboard sides, sort of a small attempt at graceful streamlining.

Most Victory ships were named for American cities, others for colleges

and

universities.

There was an old sea story, frequently repeated, about Victory hulls being built for one trip only. Perhaps this was true for the Liberty ships, but during both the Korean and Vietnam wars dozens of VC-2 vessels were taken out of the reserve (mothball) fleet and restored to service. Three of them are still alive today as museum ships.

Joliet Victory went into service late in WW II. Later it was operated as a commercial freighter by various shipping lines. It was taken out of service and joined the mothball fleet for several years, then resurrected in 1958, and converted to a deep ocean survey ship at the Charleston Naval Shipyard in South Carolina. The ship was renamed USNS Michelson after Albert Abraham Michelson who in addition to having been a US Navy commander and professor at the Naval Academy, was the first person to accurately measure the speed of light. Michelson received the Nobel prize for physics in 1907.

|

| Seagulls

on Michelson's fo'c'sl. Photo by Carl Friberg. |

Michelson was operated by the Military Sea Transportation Service (MSTS), the transport and special missions arm of the navy. MSTS ships were manned by civilian merchant marine crews. MSTS is now (since 1970) known as Military Sealift Command (MSC).

- SS Joliet Victory in Lloyd's Register

- Who was Albert Abraham Michelson?

- Michelson, Dutton and Bowditch

- What was MSTS (Military Sea Transportation Service)?

- What are non-commissioned ships?